|

RIP, Toffee. Nice meeting you.

|

Finally! I

finally finished reading something (TWO somethings!) this year, I

finally finished a pair of short books that I've been planning to pair together since I got them back in AUGUST, and I'm

finally writing a new book review for the first time in 2023. Both of the following are works of fiction that I bought on August 12th, at a Detroit independent bookstore called

27th Letter Books. I remember the date because that was the day my friend

Marlee had her farewell dinner in Detroit before moving to New York for grad school, and I made a point of spending hours browsing at 27th Letter beforehand because Marlee had been recommending that place to me for ages. (Thanks, Marlee!)

In my post-

Broken Earth recovery I tried to keep my most recent review of

Before I Let Go "brief" and... we see how that went. But I mean it this time! These reads are short (under 200 pages each), and I need to move on with my life and tackle so many other books that I've kept waiting, so I'm going to keep this review as close to my version of concise as possible. First up, a darkly humorous Mexican novel about a lawyer slowly dying from tongue cancer, and the multiple people caring for him. And then, a story collection by THE Alice Walker about Black women, mostly Southern, finding love and tragedy in the same places.

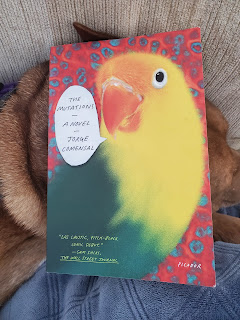

The Mutations by Jorge Comensal

(Translated from Spanish by Charlotte Whittle)

I bought this book because a dog told me to. While I was in the fiction section of 27th Letter, this was the book I happened to be contemplating when I felt a nose lightly nudging against my left leg. I looked down to see Toffee, the 14-year-old red nose pit bull who belonged to one of the bookstore employees. (I say

belonged in past tense because I just looked up 27th Letter's Instagram account and saw an

announcement from February 12th that Toffee has sadly passed away. Rest in peace, Toffee!) She was sniffing me out like she would apparently do to every customer before eventually losing interest and going off to do her own thing in the store; that day, her own thing was crying for her mom who kept popping in and out of the building to do yard work. Being intercepted by Toffee, who looked so much like an older and thinner version of my own red nose pit bull Julia, seemed as good a sign as any to take home what I already had in my hand. Since the store had so many enticing selections, and I was having trouble making up my mind anyway. Plus I'd be trying something new (Mexican literature)!

Ramón is nearly 50 years old and works as a lawyer in Mexico City. In other words, from arguing in court to charming his clients, Ramón talks for a living. Until he suddenly discovers a painful and cancerous tumor on his tongue, and the only viable treatment is to have his tongue surgically removed. Losing the ability to speak is not only the end of his law career, but the beginning of what is ultimately the final year of his life as his cancer eventually resists treatment, spreads to his lungs and elsewhere, and becomes terminal. His wife Carmela (who also previously worked as a lawyer) oversees his care at home with the assistance of the family's talkative and pious but well-meaning maid Elodia, while his teenaged children become increasingly depressed. (Mateo holes up in his room to touch himself and spend hours on the Internet, while Paulina goes from binge-eating to barely eating at all.) Meanwhile, Ramón communicates by writing things down and

making disapproving faces, and he secretly plots to set his family up to

be financially secure before dying by suicide. (Slight spoiler: Ramón does die, but not by suicide, and someone in his household has

something to do with it.) The lovebird on this book's cover represents Benito, the endangered parrot that Elodia illegally buys to cheer Ramón

up, because he's miserable and has made the household miserable as a result. And surprisingly, this works. The parrot's vocabulary consists of cuss words and dirty phrases that he loudly squawks when he's in a good mood, which is only when Ramón

is around.

Although Ramón's family features heavily in The Mutations, the chapters mainly alternate between his perspective and those of two other people who are preoccupied with the history, nature, and experience of cancer for their own complex reasons: his oncologist Dr. Aldama, and his therapist Teresa. The titular mutations in Ramón's cancer cells are bewilderingly unusual, so much so that Aldama hopes that studying them will garner him widespread acclaim for making a ground-breaking scientific discovery

(if not curing cancer, then at least reaching an unprecedented understanding of how cancer works). As for Teresa, she has a convenient excuse to never move on from her own bout with breast cancer because she now counsels cancer patients and survivors for a living. She operates her therapy practice—and her own cannabis greenhouse, administering some patients medicinal marijuana on the low because weed

isn't fully legalized in Mexico—inside her home.

I am more sentimental than I usually like to admit, which means I'm always trying to pick out some sort of meaning or symbolism from my reading experiences, and on multiple occasions I've written about feeling like I "was meant to" read a certain book at a certain time. (

The Fisher King,

Nowhere Is a Place, and the

Broken Earth trilogy immediately come to mind.) But sometimes it's just true! Like it is for

The Mutations! First, as previously mentioned, there was my encounter with Toffee, which I took as a sign to buy the book. That was in August, and I started reading the book in September. So there I was, very leisurely reading this novel about how much it sucks to be a patient, how demanding it is to be a caregiver, the obstinate mystery that is cancer, and what wisdom or raw truths or even levity can be gleaned from these very particular forms of suffering. And then, my mom wound up going in and out of the hospital every month from October to February—not because of anything quite as dire as cancer, but it was still a terrifying time. Which meant

my mom was (is kinda still) experiencing how much it sucks to be a patient, and

I was (am kinda still) experiencing how demanding it is to be a caregiver! And all the while I'm continuing to read snatches of this book about illness and suffering. I'm just saying... my whole trajectory with this book from August 2022 to February 2023 doesn't seem merely coincidental

to me! I honestly feel like God knew I would need the added humor and perspective to accompany me during what was to come, and Toffee noncommittally stepped in with the assist so that I wouldn't leave 27th Letter without those things.

Now. Given the story I just told, did I derive any sense of comfort from reading The Mutations? Distraction, release, sure. But comfort? Not exactly. The novel does aim to make readers laugh, and laugh I did. However, I don't think it's necessarily concerned with making readers—or any of the characters, for that matter—feel better. Some life events, such as a cancer diagnosis, simply suck. They might discombobulate or refine our priorities, establish a relationship of care and empathy deeper than we've ever known, and raise some excellent food for thought... but there's no definitive "feeling better" in situations like the specific ones presented in The Mutations. Jorge Comensal denies us that, and you know what? I don't mind it, because it still made me laugh. If you're interested in stories set in Mexico written by Mexican authors, literature translated from Spanish, disability and non-verbal communication caused by illness, family mess, sarcasm, abrupt endings, or why cancer does what it does and what it all means (if it means anything at all), then read this book!

Favorite quotes:

"'Why me?' asked most of her patients, as they tried to comprehend the scale of their misfortune, but Teresa, who years earlier had consigned that narcissistic question to the garbage, tried to lead them down a different path, into the basement of unfulfilled desires that fed their fear of oblivion" (17).

"Good health wasn't a state of peace and harmony with the environment, as naturopathic quack healers proclaimed. In fact, it was quite the opposite—a fleeting victory over chaos, a balancing act on a tightrope stretched over an abyss of turmoil. The 'health' touted on TV was the opium of a century of narcissists, an effective illusion for marketing vitamins, salads, and activewear, but useless for understanding the body's relationship to the world. Just like the plague and tuberculosis in other eras, cancer revealed this 'natural balance' to be a gargantuan sham, the missing clothes of an emperor not only naked but wasting away" (119-120).

"He understood her anger: she had done everything she could, and the doctor had let her down. Nevertheless, it wasn't his job to apologize like a hotel manager to an unsatisfied guest. Medicine was a rudimentary and to a large extent intuitive trade, from which it was impossible to expect perfect results" (151).

"'No, Ramón,' she said gravely, 'they're going to miss you. It'll be a huge loss for them... there's something really important you still need to do for them. Say goodbye slowly, teach them how to say goodbye. Nobody tells you this, but it's something that can be learned. My grandmother taught us how... She gave us all a gift and told us all something special. It was a master class in farewells... You can't abandon your children just like that, otherwise how will they know what to do when their own time comes?'" (166).

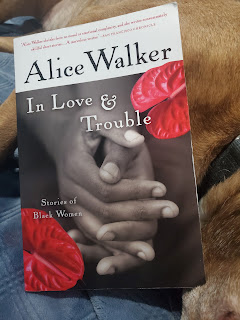

In Love & Trouble: Stories of Black Women by Alice Walker

I bought this book because I found it among the $10 shelves at 27th Letter, and I realized that the only work I'd ever read by Alice Walker was

The Color Purple. (I do have a copy of

Now Is the Time to Open Your Heart that I bought from my local library's book sale a few years ago, but it's still tucked away in my room.) No elderly pit bulls involved in my decision with this one. In 13 stories, told mostly from female characters' perspectives, Walker portrays Black women and girls who do not receive the love that they need and deserve. More pointedly, any notion of protecting their innocence, or obtaining romantic and mutually-fulfilling love with a male figure, largely takes a backseat to surviving the clutches of racism and the weight of those male figures' overbearing desires. The majority of these stories take place in the South during varying periods of the 20th century up to presumably the 1970s, given that this collection was first published in 1973. With that said, one story is partially set in New York City ("Entertaining God"), and another is set in Uganda ("The Diary of an African Nun"). I'll be focusing mostly on my favorites, which are "Really,

Doesn't Crime Pay?", "The Revenge of Hannah Kemhuff", and "The Diary of an African Nun".

"Really, Doesn't Crime Pay?" features a housewife named Myrna who's stashed away over 20 years' worth of her own secret writings. In 1958, she has an affair with a traveling writer named Mordecai after he reads and commends the quality of her ideas, only for him to steal her best work and publish it as his own in a magazine. (He left promising that he'd take Myrna's work back north with him to get it published so she could become a famous author.) The betrayal—along with the depression she'd already sunken into waiting for Mordecai's return—leads Myrna to attempt murder on her husband with a chainsaw, after which she is institutionalized. After her release in 1961 (the present), she finds ways to amuse herself until she's ready to leave her husband for good. Like secretly taking birth control pills (frustrating her husband's baby-making efforts), using his ideal of a wife against him by excessively buying clothes she'll never wear, and indulging in copious beauty products to make her skin soft and her body smell sweet. As someone who has squirreled away over 10 years' worth of songs that I've written but have let almost no one hear, I related to Myrna's sensitivity and was exceedingly amused by the petty and willful ways she chose to resist her situation.

The titular Hannah in "The Revenge of Hannah Kemhuff" is a woman who suffered public humiliation, starvation, abandonment by her husband, the deaths of her four young children, and accelerated grief-induced aging during the Great Depression. This was all because a white woman administrator refused to redeem her and her family's food stamps, claiming they were dressed too well to need help. Now in 1963, Hannah requests that a pair of rootworker women curse the now-wealthy white woman with a miserable death so that Hannah can at least die with a sense of justice, having regained some of the pride that she lost. (Spoiler: the white woman is dead within a year.) As noted in the book, this story is a tribute to Zora Neale Hurston and her 1936 book Mules and Men, which presented her anthropological research on African-American folklore. The "curse-prayer" that the rootworker women have Hannah recite twice a day for nine days is verbatim the same curse-prayer that Hurston originally included in Mules and Men. A fictional story of divine revenge, against the devastating material and spiritual consequences of racism, based around actual documentation of Black folklore? It's maddening and heartbreaking yet exhilarating at the same time!

In fact, "Hannah Kemhuff" is what finally made me pay attention to Walker's use of certain In Love & Trouble

stories to implore Black Americans to cherish rather than forsake our

traditions and ancestral knowledge. Whether that be by actually using

family heirlooms that were made to be used rather than museum-ified

("Everyday Use"),

respecting country ways of living, or even employing rootwork and home

remedies as alternative methods for obtaining the care and healing that

we have been denied ("Hannah Kemhuff" and "Strong Horse Tea"). Because

even as we've been cut off from so much of our origins, we do still have ancestral knowledge to keep passing down,

rooted in the cultures and communities we've cultivated out of necessity

in the South. Even if characters or

readers have no desire to replicate such traditions in their

own lives, the traditions and the reasons why Black people have turned to

them are still worth contemplating deeply. They're still worth remembering on purpose.

And then there's this mind-blowing stunner called "The Diary of an African Nun", about an unnamed celibate nun living and working at a mission school that moonlights as a hotel for Americans and Europeans, in an area of her Ugandan village that's set apart from her people. Having become a nun when she was 20 years old, she now reflects on her decision to convert, her

longing to partake in the festivities of her people

again, and her desire for physical intimacy that she's no longer allowed to have. She even refers to sex

as "the oldest dance", and highlights the indigenous

life-bringing sensuality of her people's dance rituals, their chanting, their goat-eating, and snow melting on the Ruwenzori mountains (wetness sliding down a hot, black mound) every spring to provide water for bathing and farming. All of this described in contrast with Christianity, specifically Catholicism in this case, which requires that Ugandans convert (dead themselves, die in spirit) or be penalized in some brutal way (suffer materially, die in the flesh). As someone caught between African (Black) and Western (white) religious

traditions, the nun questions why faith should be mutually exclusive from eroticism and reverence for the natural, and she sorrowfully acknowledges her role in subjugating her own

people through spreading the Gospel. Fully aware of how deceitful and destructive assimilation will be, she still views teaching her people to convert as her only recourse to

protect them from being completely wiped out by colonization in the forms of religion and tourism, which aren't leaving Africa or making fewer demands anytime soon. If ever.

In Love & Trouble ends with "To Hell with Dying", where an unnamed woman fondly recalls a grandfather figure from her

youth named Mr. Sweet. He was her alcoholic guitar-playing neighbor who was

beloved by many, and whom her family often "revived" whenever he came

close to dying. As children, she and her siblings

would be brought to Mr. Sweet to shower him with affection and enthusiasm that

would awaken him and make him keep living for a while longer. This continued until the narrator, as a 24-year-old doctoral student in New England, was called down home to witness 90-year-old Mr. Sweet dying for the final time. But he made sure to set aside his guitar in advance, just for the narrator to have and keep. So even if some readers might regard

In Love & Trouble as too raw, or a downer, because they were seeking something lovey-dovey or underestimated the "trouble" part of the title, Walker is gracious enough to at least conclude the collection with a story that's tragic like all the others, but also

heartwarming and... sweet. (Pun intended.) If "unlucky in love" is a vast understatement for you or the women you know, if you believe Black women and girls still deserve better than what they are given, or if you simply want to read more of Alice Walker's work, then read this book!

Favorite quotes:

"He took me in his arms, right there in the grape arbor... After that, a miracle happened. Under Mordecai's fingers my body opened like a flower and carefully bloomed. And it was strange as well as wonderful. For I don't think love had anything to do with this at all." (from "Really, Doesn't Crime Pay?", p. 17)

"I gloat over this knowledge. Now Ruel will find that I am not a womb without a brain that can be bought with Japanese bathtubs and shopping sprees. The moment of my deliverance is at hand!" (from "Really, Doesn't Crime Pay?", p. 18)

"She will read every one of the thick books in her arms, and they are not books she is required to read. She is trying to feel the substance of what other people have learned. To digest it until it becomes like bread and sustains her. She is the hungriest girl in the school." (from "We Drink the Wine in France", p. 123)

"His eyes would get all misty and he would sometimes cry out loud, but we never let it embarrass us, for he knew that we loved him and that we sometimes cried too for no reason." (from "To Hell with Dying", p. 134)