July said she got places to be, and she ain't have time for us. So here I am already at the end of another month, writing a new book review. There's no rhyme or reason to me pairing the following novels together, other than they're the two books that I've most recently finished reading. Now that I think about it, both do involve 30-somethings catching their lovers cheating and driving across multiple states to escape the drama and the hurt, and both were also written by Black authors who are currently based in Brooklyn, but those commonalities didn't occur to me before. First up, a novel about generations of Black/Native women rooted in Georgia from 1836 through the mid 1990s, as told by a descendant who writes about them while road tripping to a family reunion with her estranged mother. And then, a novel about love woes, work woes, gentrification, and friendship between three gay Black men in Detroit (their hometown).

Nowhere Is a Place by Bernice L. McFadden

I love when I go to a bookstore or a sale and take something home with me just to say I didn't leave empty-handed, while not actually expecting much, only for that very same book to blow my mind (like

If I Had Your Face did). Instances like those make me feel like I was meant to read that book at that exact point in time (like

The Fisher King did). Such is the case with

Nowhere Is a Place. In May I went to my local library to start editing

episode 98 of my podcast, and popped into the spring book sale they were having before I got started. But it was the nth day of the sale, and the pickings were slim by then. Just as I was headed out the door, I spotted

Nowhere Is a Place and recognized Bernice L. McFadden's name; I hadn't read any of her work yet, but I'd heard much acclaim about her debut novel

Sugar. And without any context, the title spoke to me in an inspirational sort of way:

Even if I feel like I'm nowhere, that's still somewhere, right? So I figured I'd make this my introduction to McFadden, and the lady at the sales table let me have it for free! She initially asked for $1, but then said it was free since it was one of the books that the library had discarded (as opposed to being donated by the public, I guess?). I'm still not sure if that's true or if she was merely in a generous mood, but either way, I took my free hardcover copy of

Nowhere Is a Place home that day, expertly-laminated jacket and all!

In her late 30s, after getting kicked out by her abusive and cheating boyfriend, Sherry drives from Chicago to a seaside fishing village in Mexico, getting an abortion and making her yearly vacation spot her refuge for the next two years. While wallowing there in her grief, she finds love again with a younger man whom she first met in her early twenties. This new love gives her the courage to come out of hiding in 1995 when, loved up with her boo and newly pregnant, Sherry is informed about her extended family's upcoming reunion in Sandersville, Georgia. With this news, she drives alone to Nevada to personally invite her estranged mother Dumpling to go on a road trip to

Sandersville with just her, separately from Sherry's

two siblings. (Sherry and Dumpling are estranged because Dumpling randomly slapped Sherry, hard, when Sherry was six years old. And while Sherry has spent her whole life hoping for an apology or explanation, Dumpling doesn't seem to remember the slap.) On the road, Sherry express her desire to write a book about their family history, and based on Dumpling's recollections and her own artistic license, Sherry starts drafting a novel based mostly on the women who came before them, including:

Lou (originally Nayeli). She's born around 1830 and raised somewhere along the Atlantic Coast in her Yamasee tribe until 1836, when she's captured by a rival tribe and sold into slavery on the Vicey cotton plantation in Georgia. As a teenager, she meets Buena Vista—a Black man enslaved by the Viceys' relatives who falls in love with Lou at first sight—they get married, and they proceed to have four children. Vicey's daughter had previously taught Lou to read as a joke, and Lou not only secretly retains that information but gives her husband and children the gift of literacy as well. Suce is their fourth child, and their only daughter who isn't sold away.

Suce. Suce and Brother (originally Jeff) are the last of Lou's children left on the Vicey (then Lessing) plantation by 1865, when Brother leads Suce and the other remaining slaves in seizing control of the plantation and holding Lessing hostage. They achieve this while having no clue about the Emancipation Proclamation or the South's defeat in the Civil War because Lessing had suppressed that information. Willie—who walks from Kentucky to Georgia after being released from slavery, and who's been seeing Suce in his dreams despite never meeting her before—is the one who informs everyone about their freedom upon his arrival that same year. Willie and Suce later get married, and once the group forges Lessing's will in order to bequeath the plantation to themselves (securing their place in Sandersville for generations to come), Suce smothers Lessing to death. She goes on to have 15 children, and the 12 who survive include a daughter named Lillie.

Lillie. A young, loose, wild woman who suddenly marries an older man (a minister) named Corinthians in 1915, using life as a preacher's wife in Philadelphia as her ticket out of a country existence in Georgia. (And her ticket away from her older brother Vonnie, who's molested her and at least two of his other sisters.) Lillie has three children with Corinthians before he dies, and after selling the church she lets loose again, decking herself out in her favorite color (red), having a love child, and frequently neglecting her kids to go party and sleep with various men. Eventually, two of her sisters have to come from Georgia to check on the children, and one of the sisters stays in Philly until Lillie dies of a mysterious illness. Then, big sis moves all of Lillie's children back to the family land in Georgia. The third of Lillie's four children is a plump little girl named Clementine, who most people call Dumpling. Dumpling, of course, grows up to be Sherry's mom.

So in the

present of 1995, Sherry in her late 30s is the great-granddaughter of someone who was enslaved until their teenage years (Suce). That's

how close the history of slavery is to her. And considering that Dumpling and her siblings were partially raised by Suce, that means Sherry's really only one generation removed from it. While reading, I noticed that all the parts with Sherry and Dumpling (which I assumed comprised the main plot) are italicized, while all the past events Sherry recounts, which take up most of the novel, are not italicized. As if to signal that the core story of this novel is actually in the past, and

even though Nowhere Is a Place opens with Sherry, she's more so our conduit to that

past. As for Dumpling, I was going to summarize her like I did the other women above, but something happens to her as a preteen that precipitates her slapping six-year-old Sherry as an adult, and it's worthwhile for people to discover that sequence of events on their own; I don't want to spoil it. Instead, I'll point out that there's this theme throughout the novel of mothers harming their children for complicated reasons, and Dumpling isn't exempt from that unfortunate legacy (or generational curse, as one might call it today). It starts with the cruelties of slavery forcing Lou to kill one of her sons as an act of mercy, extends to Suce being unaware (and then in denial) of the molestation happening in her household for years, then morphs into Lillie's vengeful spirit using her eldest daughter Lovey (Dumpling's big sister) to torment Vonnie. That torment has a devastating impact on young Dumpling, which later causes her to slap her own daughter when she's triggered by the memory of what happened.

For brevity's sake, I'll just hone in on two additional motifs that stood out to me: spirits, and the color blue. For starters, Lou is the granddaughter of a Yamasee medicine man, the spiritual leader of their village. As an enslaved woman, she's haunted by the disgruntled spirit of the son she mercy-killed for the rest of her life, developing a cancer that

swells her stomach and requires her to symbolically give birth to it on her death bed, with an "ocean" surging out from inside her as she dies. Suce regularly talks to spirits and/or herself, is similarly haunted by one of her dead children who resents dying so young, and is able to sense

when something's wrong with any one of her 12 living children. And as previously alluded to, Lillie's spirit possesses her daughter Lovey's body in order to enact succubus-style revenge against her brother (Lovey's uncle). Apparently, the spirits in the Black Lessing family are rarely at rest. And the color of that restlessness is blue. Blue is the color of the eagle-shaped granite charm that Lou's grandfather gives her as a child and that gets passed down to her female

descendants, and it's also the color of the water she expels upon her death. Blue is the color of the eyeshadow Lillie wears to offset her red outfits, and the color of the moonlight that her spirit is bathed in when Lovey encounters her. Blue is the color that Dumpling avoids for the rest of her life after being traumatized in her preteen years, to the point of never wearing the color again and refusing to dress her dolls or her children in it. And blue is the color of the beaded necklace that six-year-old Sherry is wearing when Dumpling slaps her. There's also something to be said about the recurrence of the number

12—the age Suce is when she meets Willie, the number of years Suce is

cursed by another enslaved woman to not have children after marrying

Willie, the number of Suce's children who survive into adulthood, the

age that Lovey and Dumpling are when their respective innocence is

compromised, etc.—but I figure I've expounded enough for one day.

When I started reading

Nowhere Is a Place, I expected to read about a mother and daughter settling their decades-long beef (as described by the inner jacket), and granted, Sherry and Dumpling do have a breakthrough in the end. However, I didn't expect that I'd actually be reading a story about the multi-generational impacts of slavery. And that story spoke so much to this present moment in 2022—with legal attacks on women's bodily autonomy, and Black elders' warnings of us being "one vote away from the auction block" proving to be more than mere paranoia as many conservatives try to repeal rights and recreate bondage wherever possible—that I was stunned. As gruesome as the details of

NIAP sometimes are, I'm grateful to have read it because it reminded me that I and other Black people of today (especially Black women) are not alone in our suffering. We are not the first to feel like hostages in the country of our birth, not the first to question why we're even here or wonder when things will get better without regressing. Although that reminder doesn't necessarily make me

feel better about what's going on right now, it does make me appreciate the opportunity this work of fiction provides to acknowledge our ancestors' suffering, and to honor the joy that they snatched in the midst of it all. I finished

NIAP wanting to cry for them, and I don't remember feeling this spiritually connected to a novel since

Homegoing.

NIAP is easily my second favorite read of the year (so far), after

Seven Days in June. If you've ever experienced a Black family reunion, been interested in road trips, valued the importance of "knowing someone's heart", had tension with an older relative who doesn't remember your childhood the way you do, or wanted an example of Black people taking their reparations while neither waiting for over a century nor settling for white hand-me-downs, then read this book!

Favorite quotes:

"i was torn from my somewhere and brought to this nowhere place

i felt alone in this land that was nowhere from my everywhere.

[...] time flowed on like the river

like the river, time flowed on, but i held tight to the memories of my

someplace, refusing to believe that my everywhere had always been

here in this nowhere place." (Epigraph).

"They didn't want to light kerosene lamps for light or go to church every Sunday, 'cause, shit, even the Lord rested on that day, so who was watching and listening while they sweat like pigs in the summer and froze like the ground in the winter all the while singing his praises?" (226).

"Soon? What the hell could she connect that to? Nothing more than an answer to myriad questions [...] Soon didn't mean shit. But she kept the notes anyway, just in case one day it could" (272).

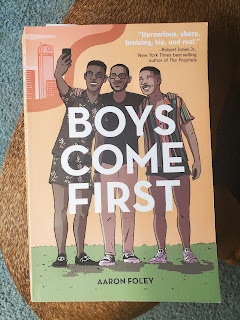

Boys Come First by Aaron Foley

I read and appreciated Aaron Foley's first book (

How to Live in Detroit Without Being a Jackass) when it was published in 2015, and I've been following him on social media for a while. So when I heard that he was putting out his first novel called

Boys Come First in May 2022, I knew I'd be reading that too!

Boys Come First was the other book I ordered, in addition to

Black Love Matters, when Barnes & Noble had their 25% off pre-order sale in late January this year. I was eager to see what Foley could do with fiction, and also eager to learn about the gay scene (especially the Black gay scene) in Detroit, according to a native Detroiter who's also a Black gay man himself.

The titular "Boys" of Boys Come First are a trio of friends in their 30s named Dominick, Troy, and Remy (DTR... D-e-T-R-o-i-t... get it?). The novel opens with Dominick, an advertising exec, driving from NYC back to his mom's house in Detroit after losing his job and catching his boyfriend of eight years cheating on the same day. He's able to secure a job at a local advertising firm to tide him over, but soon finds himself constrained by how cluelessly yet insistently white the firm is despite operating in a majority-Black city. Remy is a real estate agent and local celebrity ("Mr. Detroit") who has a roster of frequent bedfellows but desires a real relationship. As he alternates between two particular would-be boyfriends, he also has his ethics called into question after helping a pair of wealthy white developers shut down a charter school to build a ridiculously expensive apartment complex in its place. A sixth grade teacher at said school (also the main one questioning Remy's ethics and loyalty to Black Detroiters) is Troy, a half-Black and half-Bangladeshi man who proudly claims Black, and whose intention of becoming more involved with community activism inadvertently results in his being stuck in an abusive relationship with his hotep boyfriend. Troy develops a casual cocaine habit as he deals with the stress of said boyfriend, strategizing how to keep his school open, and his enduring estrangement from his rich and largely unaffectionate father.

Dominick and Troy met as high schoolers at a summer program at Michigan State University (Go Green!), whereas Troy and Remy met through a frightening incident at a party as Oakland University students. (Of all universities! Just down a few streets from me!) With Troy as the common denominator, Dominick and Remy don't become friends until Troy introduces them following Dominick's hurried return to the city. Coincidentally, Dominick becomes the new common denominator when Troy and Remy have a falling out over their opposing livelihoods. And while all three want fulfilling, committed relationships (not just sex) and fear ending up alone, Dominick is especially concerned about getting married before turning 35.

Once I read the line "with a wrinkled chitterling dick and a hog maw butthole" on page 8 and recovered from laughing myself sore, I knew I was in for a wild ride. And Foley did not disappoint! His writing is clear and concise, the dialogue is tight, not one scene is wasted, and he balances earnest sincerity with just plain silliness in a way that made me trust the directions that he chose to take Boys Come First in. As a multi-layered slice of life story, I didn't know exactly where the novel was headed in the end. I was sure that Troy and Remy would make up after falling out, and I figured Troy would overcome his shame about being abused to finally tell Dom and Remy about it. But other than that, every chapter was full of surprises, which made me enjoy BCF even more. Also, Foley deserves all the credit in the world for not shying away from writing about gay dating and sex, in multiple contexts, and in explicit detail. It's not necessarily his job to demystify those topics for readers, but I'm just saying... you might learn a thing or twelve! And the learning comes from both the horny and the wholesome; Remy talks to his little (Gen Z? Gen Alpha?) cousin Paris about being gay after Paris opens up about his interest in boys, and the eight-year-old winds up bringing some wisdom of his own to those conversations.

I was born in Detroit (raised in the suburbs), spent much of my childhood attending both of my parents' respective Detroit churches when they were were still together, spent even more time in the city when my dad (a teacher in Detroit) moved to the west side after the divorce, got my hair done in Detroit until the age of 22, and have popped in and out of Detroit for countless activities for as long as I can remember. All of that to say, while I am not from Detroit—and am mindful not to fraudulently claim the city as my own—I do know some Detroit things. Hence, I recognized many of the facets of Detroit life that Foley mentions in Boys Come First, like riding the Giant Slide at Belle Isle as a kid, or witnessing "New Detroit" white millennials dance to Motown hits at dives like the Marble Bar. (Foley is frequently gracious enough not to name certain names in BCF, but he's also brilliant at describing people, places, and phenomena in a way where those in the know can peep exactly who, where, or what he's talking about. And I just know he was talking about the Marble Bar in the opening paragraph of chapter 18. Ask me about the time in February 2020 when I went there, just around the corner from the Motown Museum, during Black History Month, and all of the DJs during this particular "Motown Music Night" were white, most of the patrons were white, and the only Black staff in the whole place were the bouncers at the front door.)

I've gotta say though, reading this book was also bittersweet. Its breakdowns of gentrification and how Detroit will inevitably continue to change (often but not always to Black Detroiters' detriment, and not to the same degree for every Black Detroiter), were sobering. And as delightful as it was for me to relate to so many of the Detroit/Metro Detroit references, it was surprisingly painful for me to read them and reckon with the fact that they're still so close to home precisely because I—despite my feverish efforts to the contrary—am somehow one of those people who still has yet to move away from their hometown (away from Michigan entirely). But that's me bringing my own personal baggage to the reading experience, obviously; that's not Foley's problem.

I was curious about why Remy is the only character whose chapters are written in first person, and it seemed a little too convenient for Troy's growing substance addiction to disappear (or at least never be mentioned again) after he learns of a loved one's grave illness. But those curiosities aside, I think

Boys Come First is a true joy! Just like how Bryan Washington's

Lot feels like a book written by a Houstonian for Houstonians,

BCF is a similar vibe but for Detroiters. Plus, what a small world!

BCF received a lovely blurb from Deesha Philyaw (author of

The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, which I still adore) on the back cover. And one of the "day-ones" who Foley names in his acknowledgements is

actually the older brother of one of the few other Black girls I knew from my Japanese

classes at MSU! (Said brother is a Wolverine, but I won't hold that

against him.) If you are interested in and/or fond of the city of Detroit, care about Black Detroiters, know about the Giant Slide, enjoy copious music references, are entertained by messiness, have ever grown apart from a close friend, or simply want to read more LGBTQ literature written by Black people, then read this book!

Favorite quotes:

"That was the first time, on the Lord's Day, when someone who wasn't blood-related to Dominick had told him they loved him.

And now, as he tried futilely to fall asleep alone in his teenage bedroom, he wondered if anyone else ever would" (17).

"The tactics were simple: scare the new white people in any way possible. If they wanted to be in Detroit, they would have to accept it all" (134).

"'I'm still all here,' she said, pointing a red fingernail to the right side of her temple. 'Some folks don't even know they're here'" (230).